Volodymyr Chekhivsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

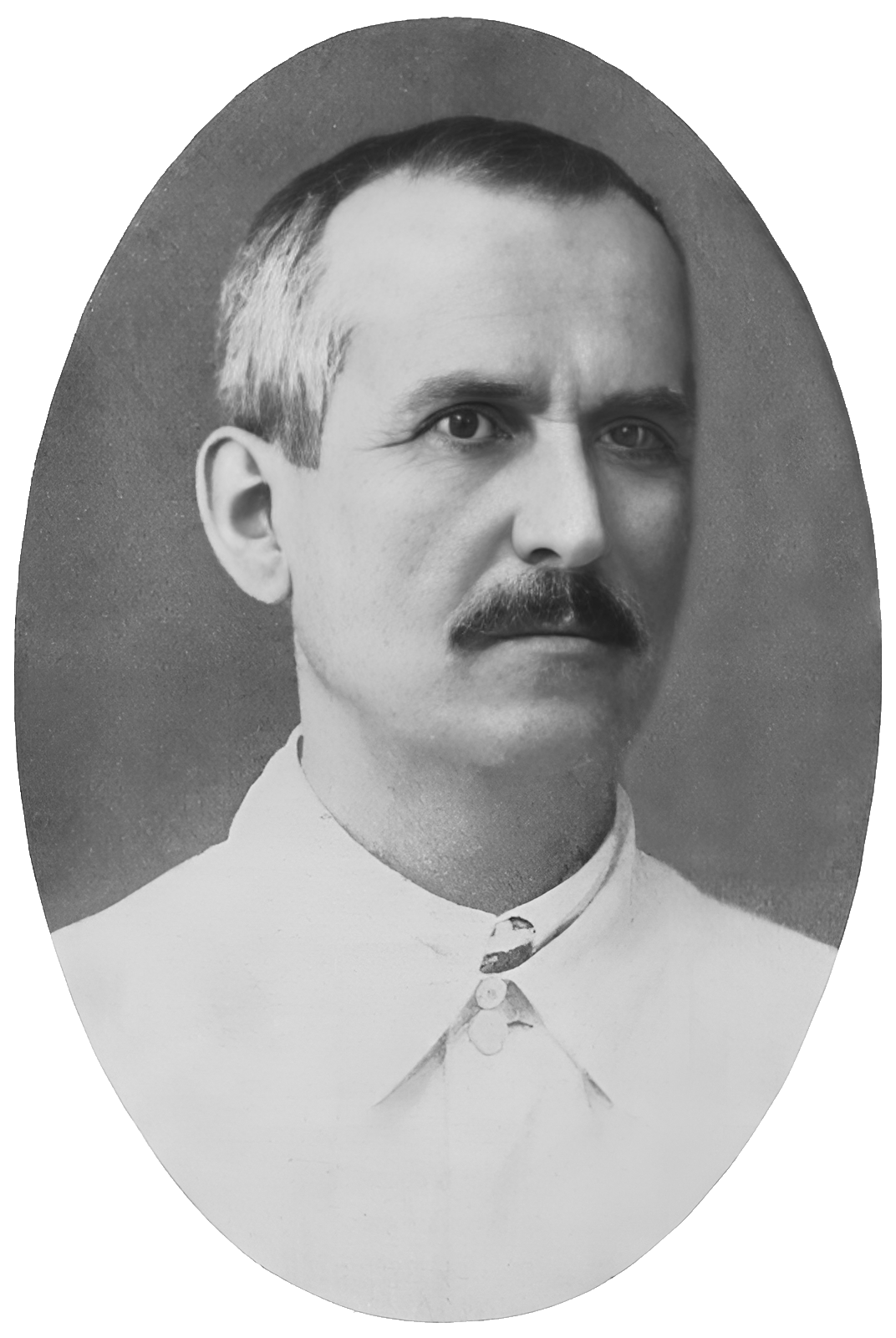

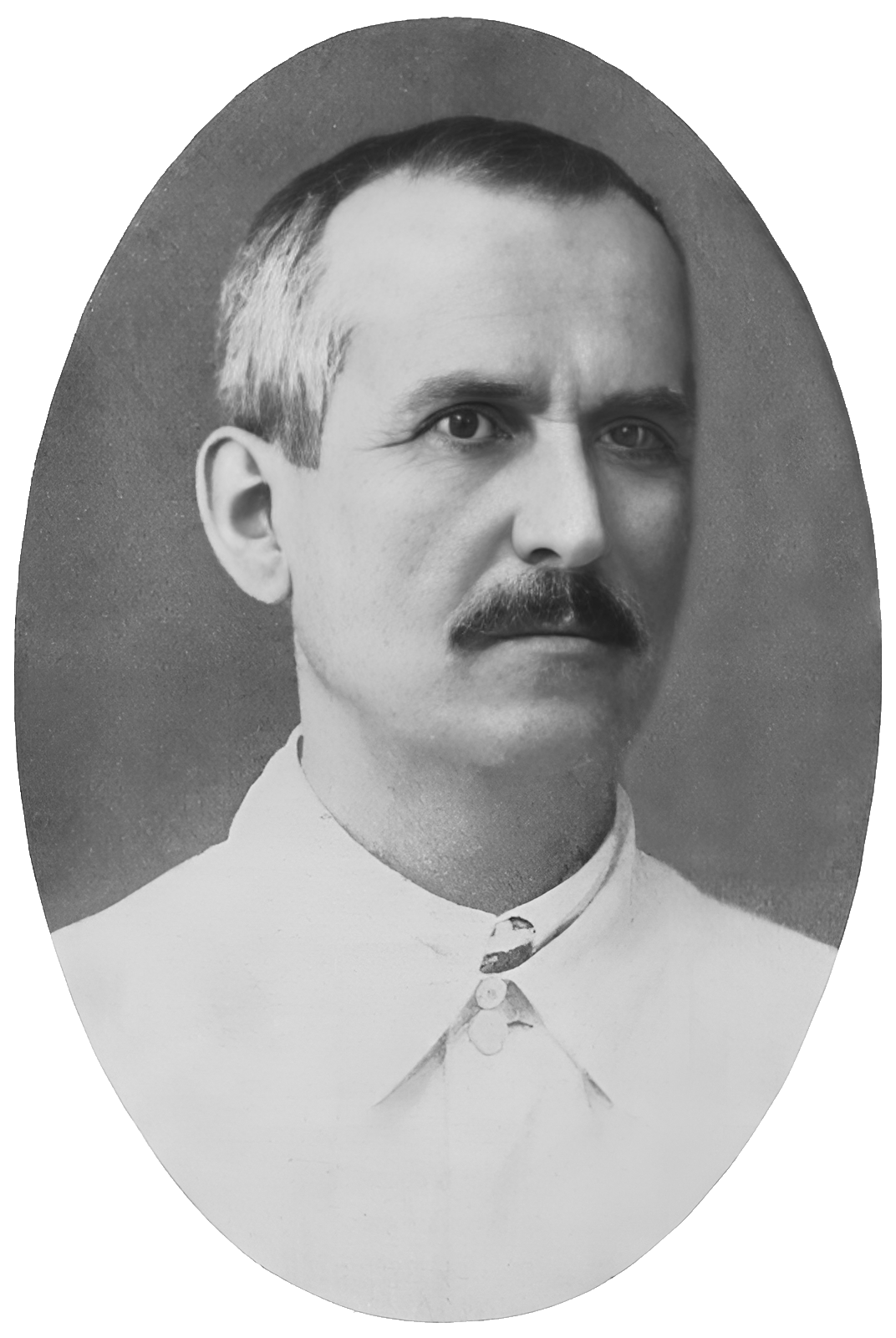

Volodymyr Musiyovych Chekhivsky ( uk, Володимир Мусійович Чехівський; russian: Владимир Моисеевич Чеховский; July 19, 1876 in

Volodymyr Musiyovych Chekhivsky ( uk, Володимир Мусійович Чехівський; russian: Владимир Моисеевич Чеховский; July 19, 1876 in

Chekhivsky: statesman, chaplain, victim of the Sandromakh tract

Chekhivsky, Volodymyr

.

Chekhivsky, Volodymyr

History of Poltava web-portal. {{DEFAULTSORT:Chekhivsky, Volodymyr 1876 births 1937 deaths People from Kyiv Oblast People from Kievsky Uyezd Ukrainian people in the Russian Empire Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party politicians Ukrainian Communist Party politicians Russian Constituent Assembly members Prime ministers of the Ukrainian People's Republic Foreign ministers of Ukraine Ukrainian writers Ukrainian educators Ukrainian revolutionaries Ukrainian diplomats Ukrainian Christian socialists Members of the Grand Orient of Russia's Peoples Kiev Theological Academy alumni Union for the Freedom of Ukraine trial Great Purge victims from Ukraine Ukrainian prisoners sentenced to death Prisoners sentenced to death by the Soviet Union Ukrainian people who died in Soviet detention Soviet rehabilitations

Volodymyr Musiyovych Chekhivsky ( uk, Володимир Мусійович Чехівський; russian: Владимир Моисеевич Чеховский; July 19, 1876 in

Volodymyr Musiyovych Chekhivsky ( uk, Володимир Мусійович Чехівський; russian: Владимир Моисеевич Чеховский; July 19, 1876 in Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate, r=Kievskaya guberniya; uk, Київська губернія, Kyivska huberniia (, ) was an administrative division of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1919 and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1919 to 1925. It wa ...

– November 3, 1937 in Sandarmokh

Sandarmokh (russian: Сандармох; krl, Sandarmoh) is a forest massif from Medvezhyegorsk in the Republic of Karelia where possibly thousands of victims of Stalin's Great Terror were executed. More than 58 nationalities were shot and bur ...

) was a Ukrainian political and public activist, prime minister of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, member of the Russian State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

, one of founders of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, Українська автокефальна православна церква (УАПЦ), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

. He was brother of conductor and singer Oleksa Chupryna-Chekhivsky.

Biography

Early years

Chekhivsky was born on July 19, 1876 to the family of aclergyman

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

in a village of Horokhuvatka, in the Kievsky Uyezd

Kievsky Uyezd (''Киевский уезд'') was one of the subdivisions of the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire. It was situated in the eastern part of the governorate. Its administrative centre was Kiev.

Demographics

At the time of the ...

of Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate, r=Kievskaya guberniya; uk, Київська губернія, Kyivska huberniia (, ) was an administrative division of the Russian Empire from 1796 to 1919 and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic from 1919 to 1925. It wa ...

(today in Obukhiv Raion

Obukhiv Raion () is a raion (district) in Kyiv Oblast of Ukraine. Its administrative center is Obukhiv. Population: .

On 18 July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, the number of raions of Kyiv Oblast was reduced to seven, and ...

). In 1900 he graduated from the Kiev Theological Academy and the University of Odessa

Odesa I. I. Mechnykov National University ( uk, Одеський національний університет Iмені І. І. Мечникова, translit=Odeskyi natsionalnyi universytet imeni I. I. Mechnykova), located in Odesa, Ukraine, i ...

, from 1905 he was a Doctor of Theology

Doctor of Theology ( la, Doctor Theologiae, abbreviated DTh, ThD, DTheol, or Dr. theol.) is a terminal degree in the academic discipline of theology. The ThD, like the ecclesiastical Doctor of Sacred Theology, is an advanced research degree equiva ...

. From 1897 he was a member of the student club of Drahomanov's Socialist-Democrats.

From 1901 to 1905 Cherkhivsky worked as Deputy Inspector of the seminaries of Kiev and Kamyanets-Podilsky

Kamianets-Podilskyi ( uk, Ка́м'яне́ць-Поді́льський, russian: Каменец-Подольский, Kamenets-Podolskiy, pl, Kamieniec Podolski, ro, Camenița, yi, קאַמענעץ־פּאָדאָלסק / קאַמעניץ, ...

. Because of his activity and interest in Ukrainian nationalism at the seminaries, Chekhivsky was dismissed and transferred to the Cherkassy Province. From 1905 to 1906 he was a teacher of Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the First language, native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European langua ...

as well as of the History of Literature and the Theory of Philology at the Cherkassy Theology College.

Between 1902-1904 Chekhivsky was a member of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party

The Revolutionary Ukrainian Party ( uk, Революційна Партія України) was a Ukrainian political party in the Russian Empire founded on 11 February 1900 by the Kharkiv student secret society Hromada.

History

The rise of the ...

, after which he switched to the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party ( uk, Украї́нська соціа́л-демократи́чна робітни́ча па́ртія, ''Ukrayínsʹka sotsiál-demokratýchna robitnýcha pártiya''), also known as Esdeky and SDP ...

(USDLP) until 1919. In 1906, he was elected to the Imperial Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times ...

, however the Russian government exiled him, as a Ukrainian to Vologda

Vologda ( rus, Вологда, p=ˈvoləɡdə) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Vologda Oblast, Russia, located on the river Vologda (river), Vologda within the watershed of the Northern Dvina. ...

in Russia. However, through the efforts of his electors to the Imperial Duma, he was returned from exile after one year.

From 1908 to 1917 Chekhivsky lived in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

where he taught in a gymnasium as well as commercial and technical colleges. During that time he was under open police surveillance. Nonetheless, Chekhivsky participated in the activities of a local Ukrainian Hromada

A hromada ( uk, територіальна громада, lit=territorial community, translit=terytorialna hromada) is a basic unit of administrative division in Ukraine, similar to a municipality. It was established by the Government of Ukra ...

and Prosvita

Prosvita ( uk, просвіта, 'enlightenment') is a society for preserving and developing Ukrainian culture and education among population that created in the nineteenth century in the Austria-Hungary Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

By the ...

association. Since 1915 he was a member of a masonic lodge

A Masonic lodge, often termed a private lodge or constituent lodge, is the basic organisational unit of Freemasonry. It is also commonly used as a term for a building in which such a unit meets. Every new lodge must be warranted or chartered ...

"Star of the East" that existed in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

and was part of the Great East of Peoples of Russia.

Revolutionary years

After theFebruary Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

Chekhivsky became editor of the "Ukrayinske Slovo" newspaper that was published in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

. From April 1917 he headed the Odessa committee of the USDLP and the Ukrainian council of Odessa. From May 1917 Cherkhivsky was a district inspector of the Odessa School Council and headed the Odessa branch of All-Ukrainian Teachers Union. From June 1917 he was a deputy () in the Odessa city duma from the Ukrainian parties, and headed the Kherson Governorate Council of united public organization.

In October–November 1917 Chekhivsky was a member of the Revolutionary committee (revkom). In November 1917 he became a political commissar of Odessa and an education commissar of the Kherson Governorate. At that time Chekhivsky was also elected to the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

(from the Ukrainian Social-Democrats of Odessa). In the beginning of 1918 he became a member of Central Committee of the USDLP and from April 1918 — appointed as director of confessions as a minister in government of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

. Under the administration of Pavlo Skoropadsky

Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi ( uk, Павло Петрович Скоропадський, Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi; – 26 April 1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, decorated Imperial Russian Army and Ukrainian Arm ...

, Chekhivsky continued to work in the Ministry of Confessions (director of General Affairs department), yet continuing to be a member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party ( uk, Украї́нська соціа́л-демократи́чна робітни́ча па́ртія, ''Ukrayínsʹka sotsiál-demokratýchna robitnýcha pártiya''), also known as Esdeky and SDP ...

. During that time he joined the Ukrainian National Union which was in opposition to the Hetman of Ukraine

Hetman of Ukraine ( uk, Гетьман України) is a former historic government office and political institution of Ukraine that is equivalent to a head of state or a monarch.

Brief history

As a head of state the position was establi ...

.

From Directorate to its opposition

Chekhivsky headed the Ukrainian revkom during the anti-Hetman uprising. From December 26, 1918 to February 11, 1919 Chekhivsky was President of theCouncil of People's Ministers

The Council of People's Ministers of Ukraine ( uk, Рада Народних Міністрів УНР) was the main executive institution of the Ukrainian People's Republic. Its duties and functions were outlined in the Chapter V of the Constitu ...

and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

of the Ukrainian People's Republic. During that time was proclaimed the Unification Act

The Unification Act ( uk, Акт Злуки, translit=Akt Zluky, , "Act Zluky" or uk, Велика Злука, translit=Velyka Zluka, label=none, ) was an agreement signed on 22 January 1919, by the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukr ...

of two Ukraines on January 22, 1919. On January 1, 1919 the government approved laws about the state language of Ukraine (Ukrainian) and about the autocephaly of Ukrainian Orthodox Church that were adopted by the Directorate of Ukraine

The Directorate, or Directory () was a provisional collegiate revolutionary state committee of the Ukrainian People's Republic, initially formed on November 13–14, 1918 during a session of the Ukrainian National Union in rebellion against Ukr ...

. On January 5, 1919 the government approved the Land law that was adopted by the Directorate on January 8.

Chekhivsky followed leftist political views, advocated compromise with Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, opposed the treaty with Entente. On those issues his position was similar to the point of view of Volodymyr Vynnychenko

Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko ( ua, Володимир Кирилович Винниченко, – March 6, 1951) was a Ukrainian statesman, political activist, writer, playwright, artist, who served as the first Prime Minister of Ukraine. ...

. Chekhivsky had a little influence on the army of Ukraine. After failing to reach an agreement with Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, successful offensive of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

and willingness of the Ukrainian leadership to negotiate with French led to resignation of Chekhivsky in February 1919. After that was in opposition to the government of Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian Peop ...

. In spring of 1919 participated in organization of the Labor Congress of Ukraine in Kamyanets-Podilsky

Kamianets-Podilskyi ( uk, Ка́м'яне́ць-Поді́льський, russian: Каменец-Подольский, Kamenets-Podolskiy, pl, Kamieniec Podolski, ro, Camenița, yi, קאַמענעץ־פּאָדאָלסק / קאַמעניץ, ...

.

Cooperation with the Soviets and arrest

After the occupation by theRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

Chekhivsky stayed in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and in 1920 joined the Ukrainian Communist Party

The Ukrainian Communist Party ( uk, Українська Комуністична Партія, ''Ukrayins’ka Komunistychna Partiya'') was an oppositional political party in Soviet Ukraine, from 1920 until 1925. Its followers were known as Ukap ...

. In October 1921 he participated in the 1st All-Ukrainian Church Assembly that confirmed autocephaly of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, Українська автокефальна православна церква (УАПЦ), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

(UAOC) and was an adviser to Metropolitan Vasyl Lypkivsky, organized pastoral courses in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

. Chekhivsky was one of the main ideologists of the Ukrainian Church autocephaly and supporter of Christian socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe capi ...

. In October 1927 he became a chairman of the 2nd All-Ukrainian Assembly of UAOC. During that time Chekhivsky also worked in the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences at its history-philology department, was a professor of medical and polytechnic institutes in Kiev, lectured at social-economical courses.

On July 29, 1929 Chekhivsky was arrested in connection with the Union for the Freedom of Ukraine process

The trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine ( ua, Процес Спілки Визволення України ; ) was a court trial considered one of the show trials in the Soviet Union.

The event took place in the Opera Theatre in ...

and on April 19, 1930 sentenced to death through shooting, changed to 10 years of imprisonment. He was confined to the Khabarovsk and Yaroslavl political prisons, from 1933 - in Solovki prison camp. In 1936 Chekhivsky was additionally sentenced to three years of imprisonment. On November 3, 1937 he was shot by sentence of the Leningrad Oblast

Leningrad Oblast ( rus, Ленинградская область, Leningradskaya oblast’, lʲɪnʲɪnˈgratskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ, , ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It was established on 1 August 1927, a ...

NKVD troika

NKVD troika or Special troika (russian: особая тройка, osobaya troyka), in Soviet history, were the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD which would later be the beginning of the KGB) made up of three officials who issued ...

.

Notes and references

External links

Chekhivsky: statesman, chaplain, victim of the Sandromakh tract

Radio Liberty

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

. 2012-06-02

Chekhivsky, Volodymyr

.

Handbook on the History of Ukraine

A handbook is a type of reference work, or other collection of instructions, that is intended to provide ready reference. The term originally applied to a small or portable book containing information useful for its owner, but the ''Oxford Engl ...

.

Chekhivsky, Volodymyr

History of Poltava web-portal. {{DEFAULTSORT:Chekhivsky, Volodymyr 1876 births 1937 deaths People from Kyiv Oblast People from Kievsky Uyezd Ukrainian people in the Russian Empire Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party politicians Ukrainian Communist Party politicians Russian Constituent Assembly members Prime ministers of the Ukrainian People's Republic Foreign ministers of Ukraine Ukrainian writers Ukrainian educators Ukrainian revolutionaries Ukrainian diplomats Ukrainian Christian socialists Members of the Grand Orient of Russia's Peoples Kiev Theological Academy alumni Union for the Freedom of Ukraine trial Great Purge victims from Ukraine Ukrainian prisoners sentenced to death Prisoners sentenced to death by the Soviet Union Ukrainian people who died in Soviet detention Soviet rehabilitations